|

Thus obituary appears courtesy of Marianne Schultz and the Royal New Zealand Ballet.

Dorothea Zaymes Ashbridge, ONZM, 1928 – 2021 Dorothea Ashbridge, ballet dancer, teacher, coach, choreographer and international ballet competition adjudicator, died in Auckland on December 30th, 2021. She was 93. More photos of Dorothea can be found here. A consummate artist with undying passion and knowledge of ballet, or as her student Douglas Wright MNZM described her, a ‘mythic character with a formidable reputation’, Dorothea shared her gifts and wisdom with thousands of professionals and students for over fifty years, always with a twinkle in her eye and polish on her nails. Prior to arriving in New Zealand in the 1960s, Dorothea danced for just under twenty years with London’s Royal Ballet, dancing many soloist roles and pas de deux, including The White Cat in Sleeping Beauty with Douglas Steuart and in works by the great ballet choreographers of the twentieth century including Sir Frederick Ashton and George Balanchine. This video can be found through this link. Born March 4th, 1928 in Cape Town, South Africa, Dorothea Zaymes was the fourth of eight children, six girls and two boys. She began her ballet studies as a young child, with her teachers commenting that she possessed a natural turn-out and thus suited for ballet. Dorothea progressed through the syllabus training of both the British Ballet Organization (BBO) and the Royal Academy of Dancing (RAD), the latter under the tutelege of Olive Deacon. In early 1946 at age 17, she left for London at the invitation of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School. Within three months she was asked to join the company, then called the Sadler’s Wells Ballet (christened The Royal Ballet after gaining the Royal Charter in 1958). The soloists in the company at this time included Margot Fonteyn, Robert Helpmann, Moira Shearer and Beryl Grey. Dorothea shared the stage with these illustrious stars of ballet in her first appearance with the Sadler’s Wells, Coppelia. The glamour of The Royal Ballet at this time cannot be underestimated. Dorothea recalled the company compared favourably to the Beatles owing to the ‘ballet mania’ the dancers were met with, both in London and on tour, with fans camping out overnight outside theatres to ensure tickets to the evenings’ performance. Along with the obligatory meetings with members of the Royal family attending a performance, the company hob-nobbed with local politicians and celebrities across the globe. A police escort to a mayoral reception in New York City was one such occasion. In August 1958 Dorothea Zaymes married fellow Royal Ballet dancer, the New Zealander Bryan Ashbridge. Their son Mark was born in 1965. Wellington-born Bryan Ashbridge studied ballet as boy with Joe Knowsley. By the time he was a teenager he was encouraged to travel to Australia to further his RAD examinations, becoming the first male New Zealand dancer and youngest, at age 13, to gain the Solo Seal. In 1947 he arrived in London to join the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. In the 1950s Bryan Ashbridge made several trips back to New Zealand as a featured artist, partnering fellow New Zealand ballerina Rowena Jackson. Soon after the birth of their son, and with both dancers ending their ties with The Royal Ballet, the family travelled to New Zealand where Bryan was offered work with the NZBC as a television producer. In 1966 ‘Dolly’, as she was known to friends in Auckland, accepted a job which her good friend Max Cryer referred to as an offer ‘out of left field.’ Embracing the challenges and opportunities on offer in this small nation of ballet-lovers, she found that her skills as a teacher and choreographer in demand. As Cryer recalled at the 2011 Tempo Dance Festival event honouring her many contributions to New Zealand dance, the television producer Kevin Moore approached Dorothea asking if she would be the choreographer for his latest project; a local entertainment programme featuring pop musicians accompanied by dancers in tight mini skirts, tall boots and long hair. C’mon!, a ‘tightly scripted black and white frenzy of special effects, pop-art sets, go-go girls and choreographed musicians’ is renowned for its entertaining and ground-breaking style that epitomized the swinging sixties. As resident choreographer for the immensely popular television music programmes, C’mon! and later Happen-Inn, Dolly put the dancers front, centre, around and above New Zealand’s most popular musical artists. As such, the popularity of go-go dancing in 1960s New Zealand can be ascribed to Dolly Ashbridge. See footage of C’mon! here. Following her television work, Dorothea participated in teaching and coaching with local ballet schools, notably Val Murray’s and Phillippa Campbell’s in Auckland, summer schools throughout the country and with the New Zealand Ballet in Wellington in 1970 for the production of Carmina Burana. At this time she became an international juror for ballet competitions in France, Japan and China. In 1971 Bryan was appointed Artistic Director of the ballet company and Dorothea worked alongside her husband as a teacher and rehearsal coach. However, within two years Bryan Ashbridge was appointed Associate Artistic Director of the Australian Ballet and left for Australia permanently. Soon after the couple divorced. Dorothea returned to Auckland and in the late 1970s her daily ballet class in central Auckland had a cult feel about it. The studio above the shops on Auckland’s lively Karangahape Road attracted a mixture of die-hard ballerinas, older professionals, child students and the young dancers of Limbs Dance Company. It was these classes that eventually led Dorothea becoming the resident Ballet Mistress for that company. The Limbs dancers, though petrified at times of her dismissive comments and tortuously difficult enchaînement, valued her commitment and perseverance in ‘whipping them into shape.’ Douglas Wright, in his autobiography Ghost Dance, likens his first encounter with Dorothea as ‘going to the dentist’ as her reputation for precision, repetition and exactitude in class was legendary and daunting. Of his first class in 1980 he recalled entering the studio and spying Dorothea ‘dressed entirely in pink, sitting in a haze of cigarette smoke at the piano, curling her eyelashes.’ Nonetheless, all of the Limbs dancers adored Dorothea and her classes left indelible marks on the careers of New Zealand’s finest contemporary dancers, too many to name here, but including Mary Jane O’Reilly, Mark Baldwin, Chris Jannides, Debra McCulloch, Susan Trainor, Shona Wilson, Shona McCullagh, and Taiaroa Royal, who called her the ‘epitome of elegance’. When she ceased teaching many of her former students created lasting and close friendships with their mentor, teacher, and, at times, harshest critic. Adroitly managed by the late Sue Paterson ONZM, Limbs attended the American Dance Festival (ADF) in Durham, North Carolina in 1981 with Dorothea an integral part of the Limbs entourage. As O’Reilly recalls, ‘a whoosh of whispers went round the campus when Dorothea arrived.’ Everyone was curious about this woman who observed classes dressed in a pink tracksuit, high heels, and full makeup. Thanks to Dorothea’s sartorial style and mysterious air, Limbs stood out amongst the myriad of dancers and teachers clad in the ubiquitous postmodern 1980s attire of ripped T-shirts, sweatpants, and bare feet. Dorothea’s association with Limbs proved to be one of the most rewarding and long lasting of any in her dance career, as she stated, ‘my time with Limbs were the most wonderful years of my life.’ Following the closure of Limbs in 1989 Dorothea was invited to become the ballet teacher for the Performing Arts School in Auckland, whose dance programme became a part of Unitec in the mid-1990s. In 2007, at age 79, Dorothea performed in Tempo Dance Festival in a duet choreographed by O’Reilly with former Limbs dancer Debra McCulloch. The still and stately presence of Dorothea coupled with the steady partnering of McCulloch was both mesmerizing and thrilling. Earlier, in 2003, Dorothea appeared in a film by Catherine Chappell and Alyx Duncan shot in the bunkers on Auckland’s North Shore. Timeless depicts three dancers at various stages in their dancing lives, the film can be found here. In her later years Dorothea, aka Thea, Doro, Dolly, enjoyed a busy social calendar, including attending performances, shopping, dining out, studying Tai Chi, and socialising with her many friends and family. She is survived by son Mark, daughter-in law Catherine, grandchildren Stella, Lucie and Jimmy and siblings Kay, Rita, Julia and George as well as several nieces and nephews. Her adopted family in New Zealand, Babe and Jack Heap, Sue and Tony Mair and their children, are especially remembered as providing shelter, support and enduring love for many decades. In 2019 Dorothea was awarded the New Zealand Order of Merit for Services to Ballet. Dorothea’s Radio New Zealand interview can be found here. Though small in stature, Dorothea’s shadow looms large over generations of dancers in Aotearoa New Zealand and her legacy lives on in the dances and dancers of today. Haere, Haere, Haere atu rā. Haere rā, e te Rangatira, ki ōu tipuna. Moe mai rā i roto i to moenga roa te rangimarie. Marianne Schultz

0 Comments

This expanded version of the obituary written by Jennifer Shennan and published in The Dominion Post online on 2 April 2022 appears courtesy of Michelle Potter...on dancing.

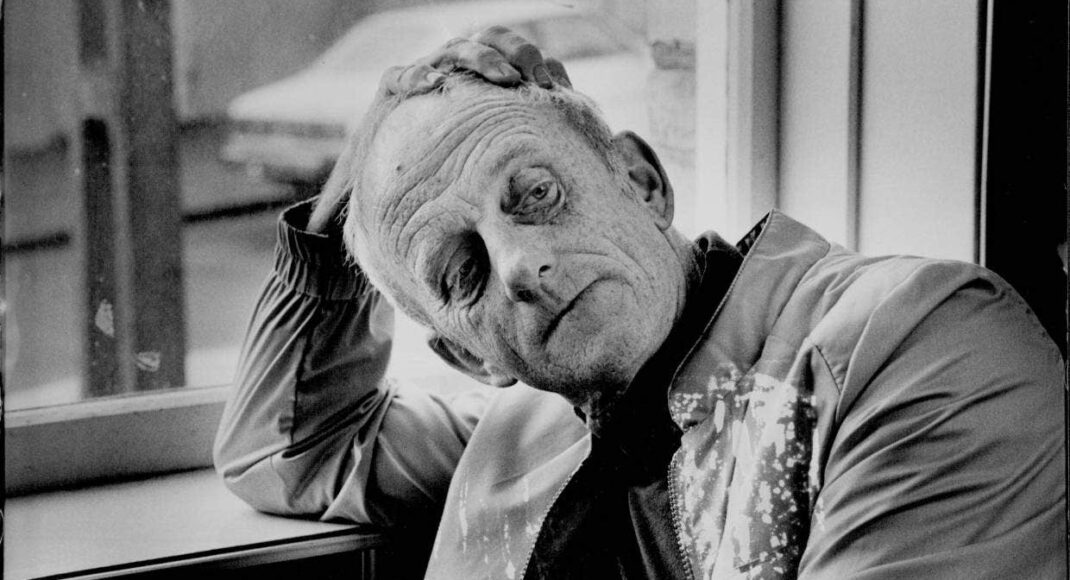

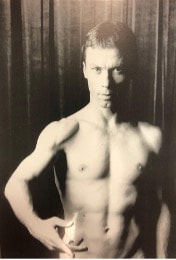

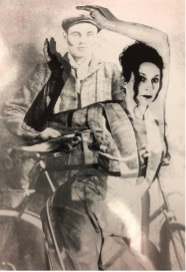

Russell Kerr, leading light of ballet in New Zealand, has died in Christchurch aged 92. The legendary dancer, teacher, choreographer and producer influenced generations of New Zealand dancers. Kerr’s hallmark talent was to absorb music so as to draw out character, narrative, human interest, emotion, poetry and comedy that ballet in the theatre can offer. Thrusting your leg high in the air, or even behind your head, just because you can, is the empty gesture of perfunctory performance that he found exasperating. Shouting and sneering at dancers, telling them they are not good enough, was anathema to him. One dancer commented, ‘Mr Kerr always treated you as an artist so you behaved like one.’ Born in Auckland in 1930, the younger of two sons, Russell was already learning piano from his mother, a qualified teacher, when a doctor recommended dance classes to strengthen against the rheumatoid arthritis that ailed the child. Did that doctor follow the remarkable career that ensued from his advice? Years later Russell was asked if it was difficult, back then, to be the only boy in a ballet school of girl pupils? He chuckled, ‘Oh no, it was marvellous—there I was in a room full of girls and no competition for their attention. It was great fun.’ Kerr made impressive progress both in dancing and piano, achieving LTCL level, then starting to teach. He could have been a musician, but dancing won out when in 1951 he was awarded a Government bursary to study abroad. In London he trained at Sadler’s Wells, with Stanislaw Idzikowski (a dancer in both Pavlova’s and Diaghilev’s companies), and also Spanish dance with Elsa Brunelleschi. Upon her advice and just for the experience, he went to an audition at the leading flamenco company of José Greco. Flamenco would be one of the world’s most demanding dance forms, both technically and musically. Remarkably, he was offered the job, providing he changed his name to Rubio Caro! How fitting that Kerr’s first contract was as a dancing musician. When asked later how he’d managed it he replied, ‘Oh, I just followed the others.’ After a time, Sadler’s Wells’ leading choreographer, Frederick Ashton, declared Russell’s body not suitably shaped for ballet. ‘I’ll show you’ he muttered to himself, and so he did. In a performance of Alice in Wonderland, he scored recognition in a review (‘Kerr’s performance as a snail was so lifelike you could almost see the slimy trail he left behind as he crossed the stage.’ As he later pointed out, ‘not many dancers are complimented in review for their slimy trails’). A sense of humour and irony was always hovering. Kerr danced with Ballet Rambert, and was encouraged towards choreography by director Marie Rambert. Later he joined Festival Ballet, rising to the rank of soloist, earning recognition for his performances in Schéhérazade, Prince Igor, Coppélia, Petrouchkaamong others. Nicholas Beriosov had been regisseur to choreographer Fokine in the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Kerr’s work with him at Festival Ballet lent a pedigree to his later productions from that repertoire as attuned and authentic as any in the world. The investment of his Government bursary was exponentially repaid when Russell, now married to dancer June Greenhalgh, returned to New Zealand in 1957. He told me he spent the ship’s entire journey sitting in a deck chair planning how to establish a ballet company that might in time become a national one. Upon arrival he was astonished to learn that Poul Gnatt, formerly with Royal Danish Ballet, had already formed the New Zealand Ballet and, thanks to Community Arts Service and Friends of the Ballet since 1953, ‘…they were touring to places in my country I’d never even heard of. So I ditched my plans and Poul and I found a way to work together.’ Kerr became partner and later director of Nettleton-Edwards-Kerr school of ballet in Auckland. (I was an 11 year old pupil there. It was obvious that Mr Kerr was a fine teacher, encouraging aspiration though not competition. We became friends for life). Auckland Ballet Theatre had existed for some years but Kerr built up its size and reputation, staging over 30 productions. Perhaps the highlight of these was a season of Swan Lake on a stage on Western Springs lake. He produced a series, Background to Ballet, for Television New Zealand in its first year of broadcasting, and also choreographed many productions for Frank Poore’s Light Opera Company. In 1959, New Zealand Ballet and Auckland Ballet Theatre combined in the United Ballet Season, involving dancers June Greenhalgh, Rowena Jackson, Philip Chatfield, Sara Neil and others. The program included Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor to Borodin’s sensuous score, and Prismatic Variations, co-choreographed by Kerr and Gnatt, to Brahms’ glorious St Anthony Chorale. Music as well as dance audiences in Auckland were astonished, and the triumphant season was repeated with equal success the following year in Wellington, when Anne Rowse joined the cast. June Greenhalgh and Russell Kerr in Prismatic Variations, 1960. Photo: © John AshtonIn 1960 a trust to oversee the New Zealand Ballet’s future was formed, and by 1962 Kerr was appointed Artistic Director. His stagings of classics--Giselle, Swan Lake, La Sylphide, The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, Coppélia, Les Sylphides, Schéhérazade—were balanced with new works, including the mysterious Charade, and whimsical One in Five. Kerr used compositions by Greig, Prokofiev, Liszt, Saint-Saens and Copland for his own prolific choreographic output--Concerto, Alice in Wonderland, Carnival of the Animals, Peter and the Wolf, The Alchemist, The Stranger. In 1964 he invited New Zealander Alexander Grant who had an established reputation as a character dancer with England’s Royal Ballet, to perform the lead role in Petrouchka, a superb production that alone would have earned Kerr worldwide recognition. A fire at the company headquarters in 1967 meant a disastrous loss of sets and costumes that only added to the colossal demands of running the company on close to a shoestring budget. Kerr’s health was in an extremely parlous state. In 1969 Gnatt returned from Australia and as interim director, with the redoubtable Beatrice Ashton as manager, kept the company on the road. Russell had worked closely with Jon Trimmer, the country’s leading dancer, and his wife Jacqui Oswald, dancer and ballet mistress. They later joined him at the New Zealand Dance Centre he had established in Auckland, developing an interesting new repertoire. The Trimmers remember, ‘…Russell would send us out into the park, the street or the zoo, to watch people and animals, study their gait and gestures, to bring character to our roles.’ Kerr also mentored and choreographed for Limbs Dance Company. The NZDC operated until 1977, though these were impecunious and difficult years for the Kerr family. But courage and the sticking place were found, and Russell, as always, let music be his guide. In 1978 he was appointed director at Southern Ballet Theatre, which proved lucky for Christchurch as he stayed there until 1990, later working with Sherilyn Kennedy and Carl Myers. In 1983 Harry Haythorne as NZB’s artistic director invited all previous directors to contribute to a gala season to mark the company’s 30th anniversary. Kerr’s satirical Salute, to Ibert, had Jon Trimmer cavorting as a high and heady Louis XIV. His two lively ballets for children, based on stories by author-illustrator Gavin Bishop--Terrible Tom and Te Maia and the Sea Devil—proved highly successful, but there was a whole new chapter in Kerr’s career awaiting. After Scripting the Dreams, with composer Philip Norman, he made the full-length ballet, A Christmas Carol, a poignant staging alive with characters from Dickens’ novel, with design by Peter Lees-Jeffries. (The later production at RNZB had new design by Kristian Fredrikson). Possibly the triumph of Kerr’s choreographies, and certainly one of RNZB’s best, was Peter Pan, again with Norman and Fredrikson, with memorable performances by Jon Trimmer as an alluring Captain Hook, Shannon Dawson as the dim-witted Pirate Smee, and Jane Turner an exquisite mercurial Tinkerbell. His sensitively nuanced productions of Swan Lake became benchmarks of the ever-renewing classic that deals with mortality and grief. Leading New Zealand dancers who credit Russell for his formative mentoring include Patricia Rianne, whose Nutcracker and Bliss, after Katherine Mansfield, are evidence of her claim, ‘I never worked with a better or more musical dance mind.’ Among many others are Rosemary Johnston, Kerry-Anne Gilberd, Dawn Sanders, Martin James, Geordan Wilcox, Jane Turner, Diana Shand, Turid Revfeim, Shannon Dawson, Toby Behan—through to Abigail Boyle and Loughlan Prior. An unprecedented season happened in 1993 when Russell cast Douglas Wright, the country’s leading contemporary dancer, in the title role of Petrouchka. He claimed Wright’s performances challenged the legendary Nijinsky. An annual series named in his honour, The Russell Kerr Lecture in Ballet & Related Arts, saw the 2021 session about his own life and career movingly delivered by his lifelong colleague and friend, Anne Rowse. The lecture was graced by a dance, Journey, that Russell had choreographed for two Japanese students who came to study with him. It would be the last performance of his work, the more poignant for that. Russell was writing his memoirs in the last few years, admitting the struggle but determined to keep going. He said, ‘Writing about my problem with drink is going to be a very difficult chapter.’ Russell had told Brian Edwards in a memorable radio interview decades back, of the exhausting time when his colossal work commitments had driven him ‘to think that the solution to every problem lay in the bottom of the bottle.’ He eventually managed to turn that around and thereafter remained teetotal for life—but by admitting it on national radio, he was offering hope to anyone with a similar burden, himself proof that there is a way out of darkness. He viewed the sunrise as an invitation to do something with the day. He would bring June a cup of tea but not let her drink it till she had greeted the sun. Recently he took great joy in seeing photos of my baby granddaughter, rejoicing to be reminded of the hope a new life brings to a family. Russell concurred with the sentiment expressed in Jo Thorpe’s fine poem, The dance writer’s dilemma (reproduced in Royal New Zealand Ballet at 60): … the thing… which has nothing to do with epitaph which has nothing to do with stone. I just know I walk differently out into air because of what dance does sometimes. Russell Kerr was a good and decent family man, loyal friend, master teacher and choreographer, proud of his work but modest by nature, resourceful and determined by personality, honest in communication, distressed by unkindness, a leader by example. A phenomenal and irreplaceable talent, he was a very great New Zealander. He is survived by son David, daughter Yvette and their families. Russell Ian Kerr, QSM, ONZM, Arts Foundation Icon Born Auckland 10 February 1930 Married June, née Greenhalgh, one son (David), one daughter(Yvette) Died.Christchurch 28 March, 2022 Sources: David Kerr, Anne Rowse, Jon Trimmer, Patricia Rianne, Rosemary Buchanan, Martin James, Mary-Jane O’Reilly, Ou Lu. Jennifer Shennan, 3 April 2022 Our Lotto NZ Story

Nga Kaitiaki Taonga Kanikani O Aotearoa The National Dance Archive of New Zealand The National Dance Archive of New Zealand (NDA) is a charitable trust formed to encourage the preservation of New Zealand’s dance heritage. We are a voluntary body which develops resources to support our dance community in preserving New Zealand’s dance scene and culture. We commission oral history recordings of prominent New Zealand dance personalities. We are not a repository for archive material, but we want to point people in the right direction. The National Dance Archive of New Zealand (NDA) has initiated several oral history projects since its inception in 1982. These recordings are deposited as part of the National Dance Archive Oral History Project with the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington (ATL Ref: OHColl-0208). Permission to listen to these recordings is required from the National Dance Archive and in many cases from other related parties. To find out if an item is available please consult the Turnbull Library catalogue or contact the Library on https://natlib.govt.nz/questions/new. Projects have covered various aspects and communities related to dance in New Zealand. This current project, A Dance Picture, is recording the life-long commitment of four women to dance and the arts in New Zealand. Although they have all been dancers in their own right, they are best known for their roles of teaching, administration and promotion of dance in New Zealand. These four women have based most of their dance career in New Zealand. Through their work they have expanded opportunities for New Zealanders in dance education and performance, and ultimately increasing audiences and dance appreciation within New Zealand. With previous oral history projects completed by the National Dance Archive having largely focused on dancers and dance teachers, this oral history project helps to broaden the spectrum of dance that has been recorded. This project is a fitting complement to the project that focused on Māori and Pasifika men in contemporary dance, as well as the celebration of the 125th anniversary of women’s suffrage. The project is of both regional and national significance, as each of these people has had a major impact on the cultural life of New Zealand, both at a regional and national level. Through teaching, mentoring and fostering the next and current generation their influence on the recognition, promotion and growth of professional dance in New Zealand has been profound. The interviewees chosen for this project A Dance Picture and generous Lotteries grant are: Carla van Zon, Jenny Stevenson, Jamie Bull, Shona McCullagh These interviews will be conducted by Lyne Pringle. Lyne has considerable experience in oral history interviewing. As dancer, choreographer, teacher, dance writer and researcher, she has a professional understanding of her subjects, a curiosity about their lives and work, and a researched knowledge of this area in New Zealand’s dance history. Since her training under oral historian, Judith Fyfe, Lyne has been the primary interviewer for five oral history projects commissioned by the National Dance Archive. In 2009, with the help of a grant from the Sesquicentennial Oral History Fund, she recorded the stories of dancers from Limbs Dance Company and Impulse Dance Company, and in 2011 interviewed Māori and Pasifika men influential in New Zealand contemporary dance. More recently, in 2013 Lyne recorded interviews with five people covering a broader perspective of the dance industry in New Zealand. The Dance Archive are extremely grateful to the Lotteries Commission for the grant that made the continuance of oral histories possible at this time. Images left to right: Douglas Wright New Zealander Dancer, Choreographer, Writer Photo: Peter Molloy Carla van Zon ONZM New Zealander Dancer, Executive and Arts Administrator Photo: Carla van Zon Shona McCullagh Dancer, Choreographer, Director Photo: Sally Tagg |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed